No matter how great we are at programming, sometimes our scripts have errors. They may occur because of our mistakes, an unexpected user input, an erroneous server response and for a thousand other reasons.

Usually, a script “dies” (immediately stops) in case of an error, printing it to console.

But there’s a syntax construct

try..catch that allows to “catch” errors and, instead of dying, do something more reasonable.The “try…catch” syntax

The

try..catch construct has two main blocks: try, and then catch:try {

// code...

} catch (err) {

// error handling

}

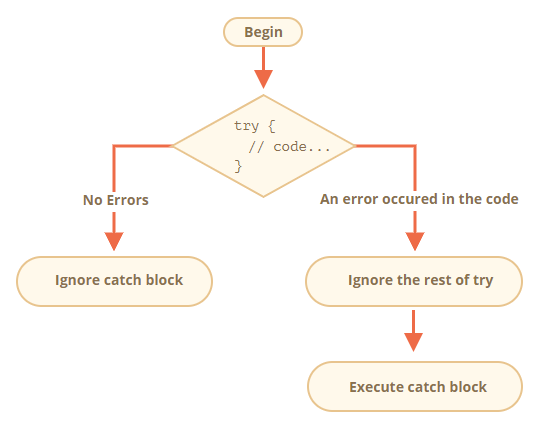

It works like this:

- First, the code in

try {...}is executed. - If there were no errors, then

catch(err)is ignored: the execution reaches the end oftryand goes on skippingcatch. - If an error occurs, then

tryexecution is stopped, and the control flows to the beginning ofcatch(err). Theerrvariable (can use any name for it) contains an error object with details about what’s happened.

So, an error inside the

try {…} block does not kill the script: we have a chance to handle it in catch.

Let’s see examples.

- An errorless example: shows

alert(1)and(2):try{alert('Start of try runs');// (1) <--// ...no errors herealert('End of try runs');// (2) <--}catch(err){alert('Catch is ignored, because there are no errors');// (3)} - An example with an error: shows

(1)and(3):try{alert('Start of try runs');// (1) <--lalala;// error, variable is not defined!alert('End of try (never reached)');// (2)}catch(err){alert(`Error has occurred!`);// (3) <--}

try..catch only works for runtime errors

For

try..catch to work, the code must be runnable. In other words, it should be valid JavaScript.

It won’t work if the code is syntactically wrong, for instance it has unmatched curly braces:

try {

{{{{{{{{{{{{

} catch(e) {

alert("The engine can't understand this code, it's invalid");

}

The JavaScript engine first reads the code, and then runs it. The errors that occur on the reading phrase are called “parse-time” errors and are unrecoverable (from inside that code). That’s because the engine can’t understand the code.

So,

try..catch can only handle errors that occur in the valid code. Such errors are called “runtime errors” or, sometimes, “exceptions”.try..catch works synchronously

If an exception happens in “scheduled” code, like in

setTimeout, then try..catch won’t catch it:try {

setTimeout(function() {

noSuchVariable; // script will die here

}, 1000);

} catch (e) {

alert( "won't work" );

}

That’s because the function itself is executed later, when the engine has already left the

try..catch construct.

To catch an exception inside a scheduled function,

try..catch must be inside that function:setTimeout(function() {

try {

noSuchVariable; // try..catch handles the error!

} catch {

alert( "error is caught here!" );

}

}, 1000);Error object

When an error occurs, JavaScript generates an object containing the details about it. The object is then passed as an argument to

catch:try {

// ...

} catch(err) { // <-- the "error object", could use another word instead of err

// ...

}

For all built-in errors, the error object has two main properties:

name- Error name. For instance, for an undefined variable that’s

"ReferenceError". message- Textual message about error details.

There are other non-standard properties available in most environments. One of most widely used and supported is:

stack- Current call stack: a string with information about the sequence of nested calls that led to the error. Used for debugging purposes.

For instance:

try{lalala;// error, variable is not defined!}catch(err){alert(err.name);// ReferenceErroralert(err.message);// lalala is not definedalert(err.stack);// ReferenceError: lalala is not defined at (...call stack)// Can also show an error as a whole// The error is converted to string as "name: message"alert(err);// ReferenceError: lalala is not defined}

Optional “catch” binding

A recent addition

This is a recent addition to the language. Old browsers may need polyfills.

If we don’t need error details,

catch may omit it:try {

// ...

} catch { // <-- without (err)

// ...

}Using “try…catch”

Let’s explore a real-life use case of

try..catch.

As we already know, JavaScript supports the JSON.parse(str) method to read JSON-encoded values.

Usually it’s used to decode data received over the network, from the server or another source.

We receive it and call

JSON.parse like this:letjson='{"name":"John", "age": 30}';// data from the serverletuser=JSON.parse(json);// convert the text representation to JS object// now user is an object with properties from the stringalert(user.name);// Johnalert(user.age);// 30

You can find more detailed information about JSON in the JSON methods, toJSON chapter.

If

json is malformed, JSON.parse generates an error, so the script “dies”.

Should we be satisfied with that? Of course, not!

This way, if something’s wrong with the data, the visitor will never know that (unless they open the developer console). And people really don’t like when something “just dies” without any error message.

Let’s use

try..catch to handle the error:letjson="{ bad json }";try{letuser=JSON.parse(json);// <-- when an error occurs...alert(user.name);// doesn't work}catch(e){// ...the execution jumps herealert("Our apologies, the data has errors, we'll try to request it one more time.");alert(e.name);alert(e.message);}

Here we use the

catch block only to show the message, but we can do much more: send a new network request, suggest an alternative to the visitor, send information about the error to a logging facility, … . All much better than just dying.Throwing our own errors

What if

json is syntactically correct, but doesn’t have a required name property?

Like this:

letjson='{ "age": 30 }';// incomplete datatry{letuser=JSON.parse(json);// <-- no errorsalert(user.name);// no name!}catch(e){alert("doesn't execute");}

Here

JSON.parse runs normally, but the absence of name is actually an error for us.

To unify error handling, we’ll use the

throw operator.“Throw” operator

The

throw operator generates an error.

The syntax is:

throw <error object>

Technically, we can use anything as an error object. That may be even a primitive, like a number or a string, but it’s better to use objects, preferably with

name and message properties (to stay somewhat compatible with built-in errors).

JavaScript has many built-in constructors for standard errors:

Error, SyntaxError, ReferenceError, TypeError and others. We can use them to create error objects as well.

Their syntax is:

let error = new Error(message);

// or

let error = new SyntaxError(message);

let error = new ReferenceError(message);

// ...

For built-in errors (not for any objects, just for errors), the

name property is exactly the name of the constructor. And message is taken from the argument.

For instance:

let error = new Error("Things happen o_O");

alert(error.name); // Error

alert(error.message); // Things happen o_O

Let’s see what kind of error

JSON.parse generates:try{JSON.parse("{ bad json o_O }");}catch(e){alert(e.name);// SyntaxErroralert(e.message);// Unexpected token o in JSON at position 2}

As we can see, that’s a

SyntaxError.

And in our case, the absence of

name is an error, as users must have a name.

So let’s throw it:

letjson='{ "age": 30 }';// incomplete datatry{letuser=JSON.parse(json);// <-- no errorsif(!user.name){thrownewSyntaxError("Incomplete data: no name");// (*)}alert(user.name);}catch(e){alert("JSON Error: "+e.message);// JSON Error: Incomplete data: no name}

In the line

(*), the throw operator generates a SyntaxError with the given message, the same way as JavaScript would generate it itself. The execution of try immediately stops and the control flow jumps into catch.

Now

catch became a single place for all error handling: both for JSON.parse and other cases.Rethrowing

In the example above we use

try..catch to handle incorrect data. But is it possible that another unexpected error occurs within the try {...} block? Like a programming error (variable is not defined) or something else, not just that “incorrect data” thing.

Like this:

let json = '{ "age": 30 }'; // incomplete data

try {

user = JSON.parse(json); // <-- forgot to put "let" before user

// ...

} catch(err) {

alert("JSON Error: " + err); // JSON Error: ReferenceError: user is not defined

// (no JSON Error actually)

}

Of course, everything’s possible! Programmers do make mistakes. Even in open-source utilities used by millions for decades – suddenly a bug may be discovered that leads to terrible hacks.

In our case,

try..catch is meant to catch “incorrect data” errors. But by its nature, catch gets all errors from try. Here it gets an unexpected error, but still shows the same "JSON Error" message. That’s wrong and also makes the code more difficult to debug.

Fortunately, we can find out which error we get, for instance from its

name:try{user={/*...*/};}catch(e){alert(e.name);// "ReferenceError" for accessing an undefined variable}

The rule is simple:

Catch should only process errors that it knows and “rethrow” all others.

The “rethrowing” technique can be explained in more detail as:

- Catch gets all errors.

- In

catch(err) {...}block we analyze the error objecterr. - If we don’t know how to handle it, then we do

throw err.

In the code below, we use rethrowing so that

catch only handles SyntaxError:letjson='{ "age": 30 }';// incomplete datatry{letuser=JSON.parse(json);if(!user.name){thrownewSyntaxError("Incomplete data: no name");}blabla();// unexpected erroralert(user.name);}catch(e){if(e.name=="SyntaxError"){alert("JSON Error: "+e.message);}else{throwe;// rethrow (*)}}

The error throwing on line

(*) from inside catch block “falls out” of try..catch and can be either caught by an outer try..catch construct (if it exists), or it kills the script.

So the

catch block actually handles only errors that it knows how to deal with and “skips” all others.

The example below demonstrates how such errors can be caught by one more level of

try..catch:functionreadData(){letjson='{ "age": 30 }';try{// ...blabla();// error!}catch(e){// ...if(e.name!='SyntaxError'){throwe;// rethrow (don't know how to deal with it)}}}try{readData();}catch(e){alert("External catch got: "+e);// caught it!}

Here

readData only knows how to handle SyntaxError, while the outer try..catch knows how to handle everything.try…catch…finally

Wait, that’s not all.

The

try..catch construct may have one more code clause: finally.

If it exists, it runs in all cases:

- after

try, if there were no errors, - after

catch, if there were errors.

The extended syntax looks like this:

try{...tryto execute the code...}catch(e){...handle errors...}finally{...execute always...}

Try running this code:

try {

alert( 'try' );

if (confirm('Make an error?')) BAD_CODE();

} catch (e) {

alert( 'catch' );

} finally {

alert( 'finally' );

}

The code has two ways of execution:

- If you answer “Yes” to “Make an error?”, then

try -> catch -> finally. - If you say “No”, then

try -> finally.

The

finally clause is often used when we start doing something and want to finalize it in any case of outcome.

For instance, we want to measure the time that a Fibonacci numbers function

fib(n) takes. Naturally, we can start measuring before it runs and finish afterwards. But what if there’s an error during the function call? In particular, the implementation of fib(n) in the code below returns an error for negative or non-integer numbers.

The

finally clause is a great place to finish the measurements no matter what.

Here

finally guarantees that the time will be measured correctly in both situations – in case of a successful execution of fiband in case of an error in it:letnum=+prompt("Enter a positive integer number?",35)letdiff,result;functionfib(n){if(n<0||Math.trunc(n)!=n){thrownewError("Must not be negative, and also an integer.");}returnn<=1?n:fib(n-1)+fib(n-2);}letstart=Date.now();try{result=fib(num);}catch(e){result=0;}finally{diff=Date.now()-start;}alert(result||"error occurred");alert(`execution took${diff}ms`);

You can check by running the code with entering

35 into prompt – it executes normally, finally after try. And then enter -1 – there will be an immediate error, an the execution will take 0ms. Both measurements are done correctly.

In other words, the function may finish with

return or throw, that doesn’t matter. The finally clause executes in both cases.

Variables are local inside

try..catch..finally

Please note that

result and diff variables in the code above are declared before try..catch.

Otherwise, if we declared

let in try block, it would only be visible inside of it.finally and return

The

finally clause works for any exit from try..catch. That includes an explicit return.

In the example below, there’s a

return in try. In this case, finally is executed just before the control returns to the outer code.functionfunc(){try{return1;}catch(e){/* ... */}finally{alert('finally');}}alert(func());// first works alert from finally, and then this one

try..finally

The

try..finally construct, without catch clause, is also useful. We apply it when we don’t want to handle errors here (let them fall through), but want to be sure that processes that we started are finalized.function func() {

// start doing something that needs completion (like measurements)

try {

// ...

} finally {

// complete that thing even if all dies

}

}

In the code above, an error inside

try always falls out, because there’s no catch. But finally works before the execution flow leaves the function.Global catch

Environment-specific

The information from this section is not a part of the core JavaScript.

Let’s imagine we’ve got a fatal error outside of

try..catch, and the script died. Like a programming error or something else terrible.

Is there a way to react on such occurrences? We may want to log the error, show something to the user (normally they don’t see error messages) etc.

There is none in the specification, but environments usually provide it, because it’s really useful. For instance, Node.js has

process.on("uncaughtException") for that. And in the browser we can assign a function to special window.onerror property, that will run in case of an uncaught error.

The syntax:

window.onerror = function(message, url, line, col, error) {

// ...

};message- Error message.

url- URL of the script where error happened.

line,col- Line and column numbers where error happened.

error- Error object.

For instance:

<script>window.onerror=function(message,url,line,col,error){alert(`${message}\n At${line}:${col}of${url}`);};functionreadData(){badFunc();// Whoops, something went wrong!}readData();</script>

The role of the global handler

window.onerror is usually not to recover the script execution – that’s probably impossible in case of programming errors, but to send the error message to developers.

There are also web-services that provide error-logging for such cases, like https://errorception.com or http://www.muscula.com.

They work like this:

- We register at the service and get a piece of JS (or a script URL) from them to insert on pages.

- That JS script sets a custom

window.onerrorfunction. - When an error occurs, it sends a network request about it to the service.

- We can log in to the service web interface and see errors.

No comments:

Post a Comment